A WALK TO WASTWATER VIA BORROWDALE, 1818

It seems that pedestrian tours through the wilder Lakeland fells were becoming significantly popular by 1818, for here's an account of another, published in a local newspaper just a few days before Miss Barker, Miss Wordsworth and co. ascended Esk Hause and Scafell Pike. My comments in [square brackets].

Westmorland Advertiser and Kendal Chronicle, 3 Oct 1818:

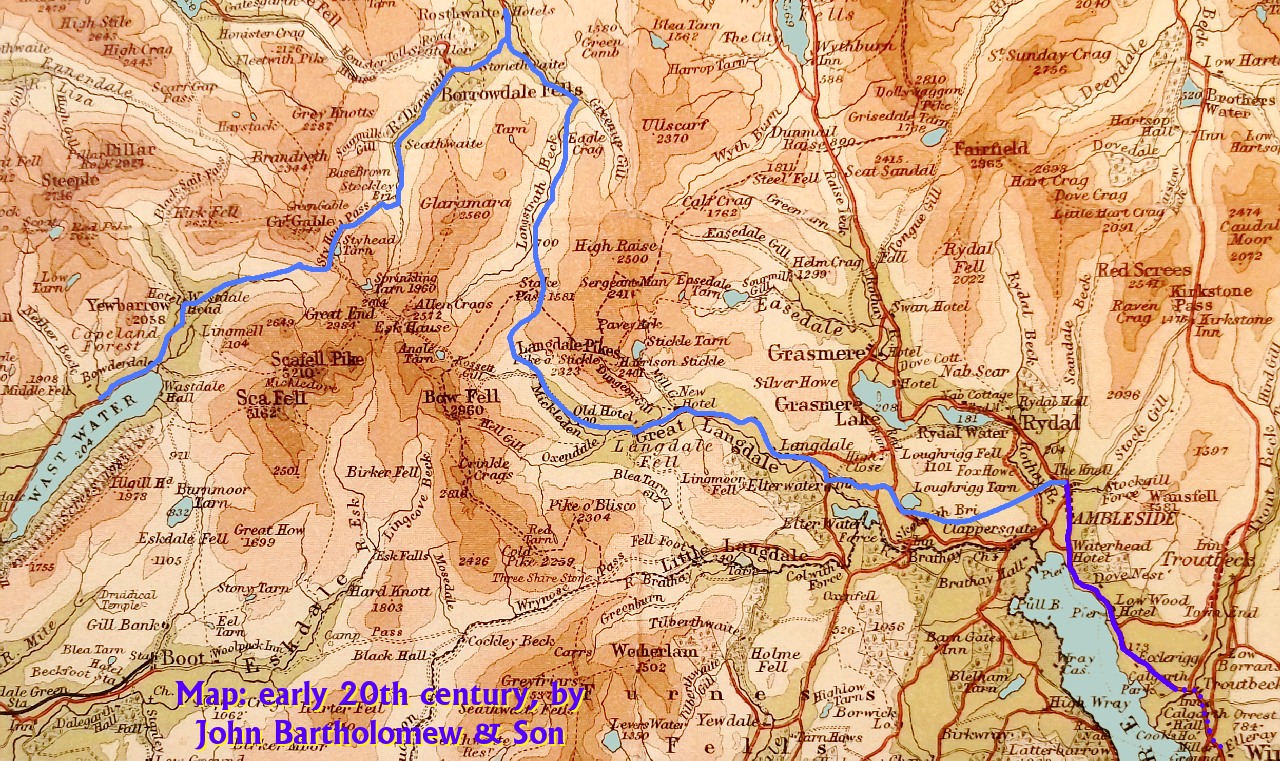

Leaving home, on the morning of September the 6th, I pursued my intended route, to Wastdale, through the Vale of Langdale, crossing the Stake, into Borrowdale, and then over Styhead, down to Wastdale Head.

I arrived at Ambleside by eight o'clock, after a pleasant and beautiful ride, along the side of Windermere, by Low Wood.- As I considered travelling on Foot the best way to see all to advantage, and having a long distance to go before night came on, I left Ambleside without making any [?dela]y; and arrived at Loughrigg Tarn by nine o'clock. The prospect here was truly grand: the morning was at first very misty; but as soon as I reached this Tarn, I beheld the clouds of mists rising out of the Vale of Langdale, adding greatly to the beauty of the Mountains. Langdale Pikes here were beautiful objects. Leaving this station with great reluctance, I pursued my journey, by Elter Water, to Langdale Chapel. The Pikes here presented themselves in bold majestic forms, and appeared to over-top the clouds - their nodding heads hung as if bidding defiance to the approach of the traveller.

From Langdale Chapel, Pavey Ark, a steep rock, said to be 600 feet perpendicular, here presented itself: in its bosom is a bason of water, called Stickle Tarn.- I passed along the sides of the Pikes, until I reached the end of the valley, or as I almost supposed, the end of the world, Langdale Pikes, viz. Harrison Pike and Pike Stickle, close to my right hand. Bow Fell was to my left and the high mountain stake reached across, so that I was compelled to make a stand, not knowing how to proceed any further. After considering a few moments, I resolved to climb the Stake, by a faint zigzag path, difficult to trace, and in some places almost perpendicular. After numerous windings, first to the right and then to the left, and many standings to take my breath, I reached the summit of the mountain. The Vale of Langdale here appeared almost under my feet, and every object before me seemed little to the eye. Taking leave of Langdale, I found I had now 7 miles to walk, before I should again see either house or field. The idea was gloomy, but what occasioned this was the apprehensions of being caught in the dark mists, which unwarily fall and prevent the traveller from pursuing his journey any further until set at liberty. I have been informed two gentlemen who were passing over this same mountain since, were suddenly covered in this dark mist, and as night was fast approaching, their only method of proceeding was by the aid of the compass. But his was a dangerous attempt, as two years ago, three Ladies passing over these mountains, through their eagerness to proceed without waiting, were almost rolled down a precipitous rock, and part of their clothes were found the day following by the shepherds. - Having, as I said before, neared the summit of the mountain, I hastened across as fast as my feet could carry me, seeing nothing but tops of mountains all around me to a considerable distance.- I now reached the other side of the mountain, down whichI proceeded in the same zigzag manner, until I came to the bottom, where I had Eagles Crag on my left, and Greenup on my right. I followed the rivulet along the valley, until I reached the village of Stonethwaite, greatly delighted to find myself once more in an inhabited neighbourhood. I here had a most delightful prospect by looking up the valley I had come along. Eagles Crag made a bold appearance, and as soon as I entered the village all seemed astonished at the sight of a stranger passing through, and gazed as if they had never seen any human being except themselves.- I asked those whom I saw if the sun shone upon this dale, the year through, they said that it did not shine upon them the whole of the winter months, and they considered it a treat to clamber up the steep mountains, during this gloomy part of the year to see it shining on a clear day.- Leaving this wild and rustic village, I soon arrived at the next, called Rosthwaite. Here I beheld the folly of an individual out of the south, building, and as he supposed [or rather, I suspect, as she supposed, this folly being almost certainly Miss Barker's], improving the country; but his notions already appeared foolish, for the whole dale, if taken to cultivate, would by no means be found adequate to support an elegant farm yard.

The day now being far advanced, I considered it time to enter some place for the night. I found a very hospitable family, with whom I spent the evening, and the conversarion principally turned upon the curiosities of the country. I informed the family my next days route was to cross the Stake, [sic] into Wastdale. They gave me information, respecting the different high mountains round Wast Water, and advised me not to attempt to climb the lofty mountain, Scawfell, as every side, to a stranger, was exceeding dangerous. I enquired respecting the nature of the mountain, and was shown some pieces of light stone, which, in appearance, fully proved the mountain at some age to have been Volcanic; they informed me that the running of the Lava was very plain to be discovered.- The conversation likwise turned upon their ideas of London, which they fancied to be, almost as Wittington supposed, paved with gold. Being much fatigued, I soon begged to retire to rest, and the family showed me up stairs, to a good bed, where I slept very comfortably.

When I awoke in the morning, every object appeared delightful by the brightness of the sun, and I hastened down to set off for Wast Dale. Having taken leave of the family, I pursued my course along the black lead mines; and from thence to Stockley Bridge, which is over a gill, along which the water descends on the southern [sic] side of the mountain, called Sprinkling [i.e. Seathwaite Fell]. This bridge is the last in Borrowdale, and is nothing more than a rude finished arch, thrown over the stream, which, by its appearance, almost forbade the stranger to attempt passing over. I here sat down and admired the curious structure of this bridge, and all the romantic scenery around- before me was the mountain, Sprinkling, upon the top of which is a tarn, wherein is a great quantity of very fine trout, said to be four pounds in weight. My course now laid up the side of this mountain, by a zigzag path, until I reached Styhead, where I saw Styhead Tarn, close upon my left: passing along the side of this, I next came to the high and almost perpendicular mountain, called Great Gable, so called from its resembling the roof of a house. I found my path lay down the side of this precipitous mountain, in a serpentine manner, for the distance of two miles. The descent was truly dangerous; I soon found that if my feet once slipped, I should immediately be hurled to the bottom, and be dashed to pieces- frequently my head was giddy, and I was obliged to halt, before I could proceed any further; but I had a most pleasant prospect of the sands of Ravenglass and Egremont [i.e Egremont Lordship], and the valley of Wast Dale appeared to the eye considerably lower than the sea. As soon as I came to the bottom of the mountain, I was greatly entertained at the sight of the shepherds standing along the foot of the mountain, called Longmell Pike [i.e. Lingmell], giving the word of command to their dogs, who were in different directions gathering their sheep into flocks. The little animals appeared to have great sagacity, and perfectly undestood the motions of the shepherds, with their crooks, whether to proceed to the right or to the left or straight forards, and what was most surprising, each dog took care to collect only its own sheep, leaving all others behind.- As soon as I entered Wast Dale, I could only find six families in all. My surprise was great, and I supposed to myself, these families would know very little of the maxims and customs of the world, and only seeing few strangers, their ideas must of course be very contracted. My curiosity lead me to enter one of their abodes, where I was received with great marks of hospitality. As soon as I was seated on a rough wooden chair, I began to enquire into their mode of living, and the nature of their trade. I was informed they sold their wool to the manufacturers, who visited them once in the year. And when sheep salving approached it was the period of their going to a market sixteen miles distant, to sell their firkin butter, and to bring home a supply of necessaries for the whole year, such as candles, soap, &c. I had not sat long, before I was greatly surprised by a number of visitors, such as ducks and pigs. I soon learnt their business, for immediately there was placed before them, on the floor, in an adjoining kitchen, a quantity of boiled potatoes. I enquired if they did not go to market to sell their ducks,- they answered that they lived upon those, besides their other produce, such as sheep, corn, and potatoes.- I asked many qustions wit a view to ascertain their conduct towards each other, in this sequestered Dale, the result of which was, that they lived as one family, and never disputed. I asked them what distance they were from a public house,- they said there was one about six miles distance, towards Ravenglass, and this road they understood little about.- I enquired what sorts of liquors they drank, and I soon learnt they considered milk the most nourishing.- I asked what they would think of seeing a public house full of beastly men, and even women amongst them, making themseles raging drunk, and at last turning out into the street to fight and bruise each other to pieces;- they seemed quite alarmed when I stated scenes which I assured them were frequently seen in my own town, and I was obliged to wave the subject immediately, and they appeared as if they suspected I was one of this inhuman and wicked tribe of beings. All worldly amusements, such as plays, gambling, racing and wakes, they seemed scarcely to know the meaning of, so that I was obliged to leave the subject altogether, to save my credit, and turn the conversation to better things.

My time going over fast, I took leave of these happy people, and visited the lake. I had a fine prospect from Over-beck Bridge of the lofty mountain Scawfell, 3100 feet high, and the Gable 2926 feet, down the steep side of which I had descended into the Dale. The high conical and sharp-topped mountain, Yewbarrow, was close to my left hand, and it appeared almost an impossibility to ascend it.- The Screes was upon my right, down the front of which I could perceive loose shining stones, continually tumbling into the lake, close under its perpendicular, and in some places, over-hanging top. I sat down, viewing this grand and beautiful scenery, for a considerable time, and I admired all around me. Many fanciful ideas crossed my mind, respecting this secluded part of the world, and its retired inhabitants, which, if properly examined, might only prove imaginations. The sun shone beautifully. Its rays pierced through the mists rising up the mountains, and all seemed to invite the traveller not to depart.

Having now taken my fill of Wast Water and the Dale, I determined to return by the same road I came. I passed the Little Chapel- its height was scarcely sufficient to allow a person to stand upright. Looking into the inside, I was greatly struck with the neat and elegant pews, which I counted to eight, and the doors of each were numbered; in this small building those six families assembled every Sabbath day, for worship. On one side of the building was [?to] be seen, the Apostles' Creed, on the other, our Lord's Prayer, and behind the Communion, the ten Commandments.- My mind really led me to suppose I was in a happy country, and I envied the place and its inhabitants. I now hastened on my journey back, but with very great reluctance all seemed to the eye so pleasant and beautiful. The thermometer here was 72. I began to climb up the Gable; and after a long gaze on all I was leaving below, I took a final leave, and hastened to the top of Styhead. Thermometer 48. The great change I felt in the atmosphere made me very shivery, and I was obliged to run as fast as I could, over the mountain; and descended again into Borrowdale, and there took my rest for the night.