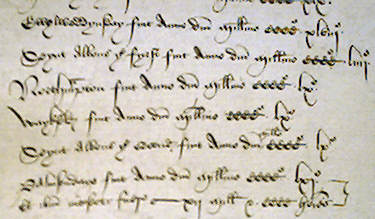

The point of the Document Challenge featured on the former home page of this little website was to demonstrate a bit of lateral thinking about forgery. The document in the Challenge, like the Kensington Runestone, has a number of features that arouse suspicion, such as incorrect dates and names for battles which, at the alleged time of writing, would have been quite recent. Assume, for present purposes, that the document is genuine, but that I am about to make a forgery, using it as a model. The forgery would end up with a text containing suspicious elements which were actually perfectly genuine!

The point of the Document Challenge featured on the former home page of this little website was to demonstrate a bit of lateral thinking about forgery. The document in the Challenge, like the Kensington Runestone, has a number of features that arouse suspicion, such as incorrect dates and names for battles which, at the alleged time of writing, would have been quite recent. Assume, for present purposes, that the document is genuine, but that I am about to make a forgery, using it as a model. The forgery would end up with a text containing suspicious elements which were actually perfectly genuine!If the original document belonged to my family, and had never been studied by scholars, how would anybody know its relationship to the forgery? In effect, we can turn the mystery of the composition of the Kensington Rune Stone text right round, and say that if it was forged, the forger chose these particular runes and this particular dialect, because he (or she) had access to one or more genuine examples which had not (and probably still have not) been seen by all those meticulous scholars. One thing this would explain is the rather stilted prose of the Runestone, which sometimes reads as if the writer is trying to express ideas using a very limited vocabulary (e.g. "red with blood and dead" instead of "hacked to death" or whatever). Interestingly, a couple of documents have recently been found, purportedly written by two teenage brothers in Sweden in the 1880s, showing two runic alphabets they had seen, including both runes and numbers almost exactly as used on the Kensington stone. Although the runic alphabets were said to be very old, they could not be, as one was designed to provide runic signs for all the letters of the 19th century conventional alphabet, including some which had not been used in the middle ages. |