A SUMMER'S EXCURSION

In Letters from a Lady to her Friend in London

The two letters transcribed here are taken from the November and December 1781 issues of the Cumberland Magazine, published in Whitehaven. Beyond what they tell us, the identity of the tourists remains a mystery- it is impossible even to be certain whether "dear Mr. ___" is Lucinda's husband, or, rather more intriguingly in an 18th century context, her boyfriend. Although she expects to visit the friend in London to whom the letters are written, the fact that Warwick is the first stop on the tour suggests that Lucinda herself may have a home out in the countryside to the north of the capital. The inclusion of the date "Wednesday July 15" implies that the trip did not take place in 1781, but probably in 1778.

N.B. The Cumberland Magazine, published monthly from 1778 to 1781, was a general-interest digest, and actually contained very little material specifically about Cumbria.

| Although the armour may have belonged to Guy de Beauchamp, 10th Earl of Warwick (1278 – 1315), the most famous Guy, Earl of Warwick, was a legendary figure who allegedly lived several hundred years earlier, in Anglo-Saxon times, and whose story was told in a 13th century poem (plus many other later versions) |

| The novel "The Widow of the Wood", by Benjamin Victor, published in 1755, was a thinly-disguised account of a real scandal involving Anna, the widow of John Whitby of Cresswell Hall, Staffordshire, and her complicated marital relationships over the few years following his death in 1750, involving Sir William Wolseley, John Robins of Stafford, and a Mr Hargreave, whose son by a previous marriage, the eminent conveyancing lawyer Francis Hargreave, allegedly attempted to acquire and destroy every copy of the novel. She was still alive in 1781. PS- somewhere in the middle of all that fits the Rev. William Corne of Tixall, who reportedly died of a broken heart... |

| "Chartres" was Colonel Francis Charteris (c1640-1732), whose gambling success against fellow-officers led to a court-martial but made him so much money that disgrace was irrelevant. He acquired Hornby Castle in 1713. |

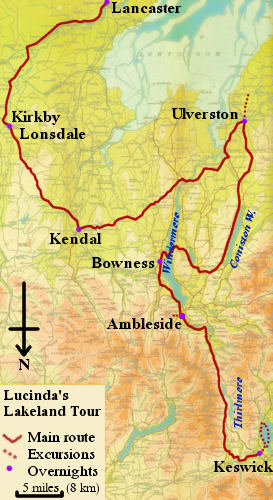

Having now given you a general account of this wonderful country, I will proceed to a journal of our progress in it. On Wednesday, July 15, we left Ulverstone, with a kind friend for our guide. The first four miles lay thro' a wild hilly country to Lowick-bridge; there we stopped to see a large forge, where they work the iron into bars. The great hammers, the bellows, and all the machinery is moved by water; and the whole seemed a good representation of Vulcan's forge, where he makes thunderbolts for Jupiter, as described by the poets. From thence we proceeded by Coniston-water: the road, which was very good, lay on the margin of the lake, which is six miles long, and a mile broad. On the right-hand we had a hanging wood, through a part of which the road lay, where it bordered the lake, and which it sometimes concealed from us; but ever and anon it would open to our view again with fresh beauty. On the left hand we had the lake, smooth as a mirror; and, on the other side of it, lofty mountains, with a striking view of the rough, ragged, rocky Coniston-fells, for four or five miles together. Between the feet of those and the borders of the lake are rich pastures, groves, and inclosures, interspersed with white farm-houses and cottages; and, at the head of the lake, on a rising hill, stands the village of Coniston, which overlooks and completes this beautiful landscape.

Having now given you a general account of this wonderful country, I will proceed to a journal of our progress in it. On Wednesday, July 15, we left Ulverstone, with a kind friend for our guide. The first four miles lay thro' a wild hilly country to Lowick-bridge; there we stopped to see a large forge, where they work the iron into bars. The great hammers, the bellows, and all the machinery is moved by water; and the whole seemed a good representation of Vulcan's forge, where he makes thunderbolts for Jupiter, as described by the poets. From thence we proceeded by Coniston-water: the road, which was very good, lay on the margin of the lake, which is six miles long, and a mile broad. On the right-hand we had a hanging wood, through a part of which the road lay, where it bordered the lake, and which it sometimes concealed from us; but ever and anon it would open to our view again with fresh beauty. On the left hand we had the lake, smooth as a mirror; and, on the other side of it, lofty mountains, with a striking view of the rough, ragged, rocky Coniston-fells, for four or five miles together. Between the feet of those and the borders of the lake are rich pastures, groves, and inclosures, interspersed with white farm-houses and cottages; and, at the head of the lake, on a rising hill, stands the village of Coniston, which overlooks and completes this beautiful landscape.

| The 3rd Earl of Derwentwater was beheaded for high treason. In 1735 his forfeited estates in Cumberland and Northumberland were donated by the Government to fund the Greenwich Hospital. |

| There was a giant called Argus in ancient Greek mythology with a hundred eyes |