EDMUND BOGG- ESKDALE IN THE 1890s

Edmund Bogg's "A Thousand Miles of Wandering...", chronicling his tours in the Borders and northern England, was originally published as a single weighty tome, but in 1898 was split into two volumes. The first of these extracts from volume 2 tells of his adventures in Eskdale (be warned that his historical information is cribbed from guidebooks, and is not reliable).

Now down the charming old lanes and byways, and up the rough path which crosses the fells yonder, we drop down to Boot, at the head of Eskdale. Near to, in the wood, is an ancient sawmill, its motive power gained from an antique water-wheel; the structure is charmingly hidden in trees, and grown over with lichen and grey and golden moss, the sunlight playing hide-and-seek on the old roof and wheel, forms a charming picture. Near to is a picturesque bridge of one span, roughly built together, and almost choked with creeper and ivy. Boot is a small rural dale-village, primitive enough to please the most fastidious. In the walls of some of the. cottages large boulders of natural rock have been utilized in the construction of the homestead. On our visit the sports were being held, which comprised racing, wrestling, throwing the hammer, the fell race, the high leap, the long leap, putting the stone, hitch and kick, the old Hellenic game of quoits, in fact all the old Scottish athletic games, except tossing the kaber, a six or more yards pole, or young tree; the base resting on the palm of the athlete's hand, supported against his shoulder, he runs in semi-bent form, to make it fall on the ground on its base- that is the feat of tossing the kaber.

Now down the charming old lanes and byways, and up the rough path which crosses the fells yonder, we drop down to Boot, at the head of Eskdale. Near to, in the wood, is an ancient sawmill, its motive power gained from an antique water-wheel; the structure is charmingly hidden in trees, and grown over with lichen and grey and golden moss, the sunlight playing hide-and-seek on the old roof and wheel, forms a charming picture. Near to is a picturesque bridge of one span, roughly built together, and almost choked with creeper and ivy. Boot is a small rural dale-village, primitive enough to please the most fastidious. In the walls of some of the. cottages large boulders of natural rock have been utilized in the construction of the homestead. On our visit the sports were being held, which comprised racing, wrestling, throwing the hammer, the fell race, the high leap, the long leap, putting the stone, hitch and kick, the old Hellenic game of quoits, in fact all the old Scottish athletic games, except tossing the kaber, a six or more yards pole, or young tree; the base resting on the palm of the athlete's hand, supported against his shoulder, he runs in semi-bent form, to make it fall on the ground on its base- that is the feat of tossing the kaber.

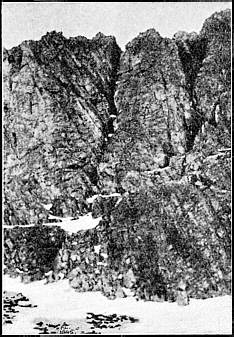

The scenery of Eskdale is finely diversified, a grand foreground of mountains, from whence the river winds through a wildly-romantic valley to the sea, near Ravenglass. Rock, hill, knoll, river, stream and cascade- fellsides clothed richly with gorse; large patches of unreclaimed moorland, where the heather blooms and wild fruit ripens; huge crags on wbich the broad leaves of ferns wave and festoon gracefully ; glades of firwood, oak, birch, and hazel skirt the hillsides, and silvery glimpses of rivers winding to the Solway, at full tide the waters swelling to a great width. Most of the homesteads are of primitive construction, chiefly of unhewn stone, and roofed with thick slate; generally, these old houses have an ample porch, and the walls, if not newly whitewashed, partake of a grey, sober aspect, and harmonise and blend with the surrounding landscape. Many genteel residences have sprung into existence of late years, and such are generally too obtrusive, and tend to destroy the romance and poetic charm of Eskdale. The little miniature railroad, however, seems almost to add to, instead of destroy, the dignity and beauty of the district; its entire length is under eight miles. It is an independent railway, and has six stations between Boot and Ravenglass; the gauge of the line is only 3 feet. The stations are curious-looking places, something like a platelayers' shanty, and are opened and closed as the train arrives and departs. One of them is composed of an old boat turned partly over (see illustration). The guard performs several duties besides his own, being station-master, ticket distributor, collector, and porter. He is most obliging, and should a likely passenger be descried anywhere within, say a quarter of a mile, he will draw up the train, whose speed generally averages eight miles an hour, to ascertain whether or not he is going up This is not fiction, for we have been so obliged.

The writer on one occasion was passing from Wasdale to Eskdale, just when the sun was setting behind the darkening hills, expecting to arrive at Boot in time to catch the last train for Ravenglass, but after hurrying and several times mistaking the path in the gathering gloom, arrived only to find the last train had gone, the station in darkness, and not a sound or a vestige of humanity around. I was obliged to be at Ravenglass that night, and not being acquainted with the road, walked the entire distance, 8 miles, in the dark, up the line. It was a murky, damp, yet warm night, and the host of glow-worms which lighted their innocuous fires on that memorable tramp I shall never forget. The shy little creatures shone with a phosphorescent brilliance most bright and dazzling, which now and again startled me, not being familiar with the soft and luminous glow of almost unearthly light, lustrous as the gems of Golconda. On and on I tramped, under beetling rock and over moor, here and there to the sound of a stream rushing under the line, until I arrived at Ravenglass, none the worse for my adventure; it was an experience I shall not soon forget. When the anxiety subsided, and reflecting on the gain I possessed, I was more than compensated for the toil and discomfort of that walk up the Eskdale line.

The writer on one occasion was passing from Wasdale to Eskdale, just when the sun was setting behind the darkening hills, expecting to arrive at Boot in time to catch the last train for Ravenglass, but after hurrying and several times mistaking the path in the gathering gloom, arrived only to find the last train had gone, the station in darkness, and not a sound or a vestige of humanity around. I was obliged to be at Ravenglass that night, and not being acquainted with the road, walked the entire distance, 8 miles, in the dark, up the line. It was a murky, damp, yet warm night, and the host of glow-worms which lighted their innocuous fires on that memorable tramp I shall never forget. The shy little creatures shone with a phosphorescent brilliance most bright and dazzling, which now and again startled me, not being familiar with the soft and luminous glow of almost unearthly light, lustrous as the gems of Golconda. On and on I tramped, under beetling rock and over moor, here and there to the sound of a stream rushing under the line, until I arrived at Ravenglass, none the worse for my adventure; it was an experience I shall not soon forget. When the anxiety subsided, and reflecting on the gain I possessed, I was more than compensated for the toil and discomfort of that walk up the Eskdale line.

Muncaster Hall, originally spelt Mulcastre, stands on a rising green plateau, charmingly surrounded and completely hidden, even at a few yards distance, by the forest. Its walls, partly covered with ivy, with battlemented roof, presents a commanding and pleasing picture. The place received its name from a Roman camp, which stood a few hundred yards nearer the sea. Near to this camp are the remains of a Roman villa; the walls still standing measure some twelve feet in height, being the highest fragment of Roman work in Great Britain. After the departure of the Romans, it is supposed to have been the residence of a British prince, for Camden states that a certain king (Evelin) had his palace here, of whom abundant stories are told. The situation is fine, close to the Solway shore, with the tidal estuaries of the Esk and the Mite to the north and south.

Muncaster Church is delightfully situated in a setting of nature's handiwork. The churchyard contains a short Saxon or runic cross. There are numerous monuments and memorials to the Pennington family; several of the brasses are very ancient. These commemorate Sir William Penyton, 1301; William Penyton, 1390; Syr William Penyngton, Knight, 1533; William Penyngton, Armr, 1543. One inscription is still in its original place, on a freestone slab in the floor of the chancel. It covers the remains of "Syr John Penyngton, sone of John Penyngtone, grandchild of ye Syr John who resseved Holye Kinge Harrye at Molcastre... He was a brave captain ... he stoutlie headed his souldiers at Floddon Field. Died MDXVIII."

Ravenglass stands by the coast, about a mile away. It is a poorly-built place, and, when the tide is low, with long stretches of sand and mud banks. Yet the varying hue of the water towards eventide is most exquisite. A century ago the village was the resort of smugglers, who ran their contraband cargoes under cover of night amongst the sandhills or numerous creeks adjoining.

Waberthwaite is a secluded little hamlet situated on the south side of the Esk, near to where it falls into the sea. The original settlement was made by an ancestor of the Wayberghs, now Whyberghs; hence we have Wayberghthwaite. During the restoration of the church, several fragments of an earlier structure, probably Saxon, were found. One of these is the shaft of an ancient cross, upon which is the figure of an animal struggling in bonds. There are also other fragments, all of which suggest a tenth century date. The font is of very primitive workmanship; the old pulpit, still in use, was the gift of Abraham Chambers, 1670. The church is prettily adorned by trees, and a few gaunt Scotch firs lend character and contrast When the Esk is at full tide, the water washes up to the churchyard. A more peaceful and secluded place would be difficult to find. The living is in the hands of the Penningtons of Muncaster, and until 1844, the parson at this place fulfilled the duties of both parishes. Up to the above date, the service was held in the morning at Waberthwaite, "of a suitable time and length" to allow the rector to cross the river Esk by the stepping-stones "free of tide," so as to be able to perform his duties in the afternoon at Muncaster.

Eskdale is full of beautiful and interesting places, on which time will not allow us to dwell longer. We must hurry over Birker and Ulpha Moor, by way of Crosbythwaite, to the vale of the Duddon. This is a long and rather uninteresting tramp across a wide moorland waste, until we drop through the wood and hazel-fringed lanes, and the beautiful valley of the Duddon, with the stream winding under the trees to the sea, spreads before us.