William Cauchi and the Ratty, c1919-23

In issue 154 of the the R.& E.R. Magazine (Sep 1999) appeared an article by John W.E. Helm entitled "More light on Cauchi and the early years 1922-23". This was based on a file in the National Archives at Kew (ref. MT 6/3462) about complaints of dangerous working on the railway at that time. Having now seen the file for myself, and copied most of the key documents, I present here a slightly different interpretation, with some more quotations, plus (in belated answer to a request John made in the article) local newspaper accounts of the accident which began the unpleasant business.

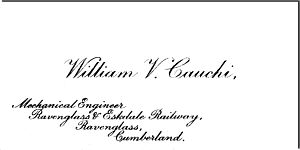

Among the many colourful characters responsible for the rise of "La'al Ratty" from the ashes of "Owd Ratty", one of the oddest is William V. Cauchi. According to the General Register Office index, William Vincent Cauchi was born in the Croydon Registration District in the September quarter of 1877 (vol.2a page 181, if anybody wants to order a copy of the birth certificate). The 1901 census has William (age 23, born at Anerley in Surrey, no declared occupation) living in Eastbourne with Michael (age 63, born in Valletta, Malta, now living on independent means) and Catherine (age 52, born in Dover). It's possible that William was then studying for his eventual career. After some years of practical railway experience he set up as a consulting engineer, and in that capacity was hired by Narrow Gauge Railways Ltd., parent company of the R.& E.R. (straying somewhat from his business card, he would often style himself "Engr. & Loco. Supt." when signing letters). As the railway's historians record, largely on the basis of recollections by then-apprentice Peter le Neve Foster (see R.& E.R.P.S. Newsletter 9, or page 41 of "The Bedside Ratty", compiled by W.J.K. Davies, 1974), Cauchi was utterly out-of-place in the happy-go-lucky Ravenglass environment- he even chose to stay at Barrow-in-Furness rather than Ravenglass when he visited the area. Arguably it was a good idea to have a responsible person among all the boys tinkering with their toys- but for all his seriousness and safety-consciousness, Cauchi simply did not have authority. His dire warnings were ignored, even after Easter 1922 when this happened:

Among the many colourful characters responsible for the rise of "La'al Ratty" from the ashes of "Owd Ratty", one of the oddest is William V. Cauchi. According to the General Register Office index, William Vincent Cauchi was born in the Croydon Registration District in the September quarter of 1877 (vol.2a page 181, if anybody wants to order a copy of the birth certificate). The 1901 census has William (age 23, born at Anerley in Surrey, no declared occupation) living in Eastbourne with Michael (age 63, born in Valletta, Malta, now living on independent means) and Catherine (age 52, born in Dover). It's possible that William was then studying for his eventual career. After some years of practical railway experience he set up as a consulting engineer, and in that capacity was hired by Narrow Gauge Railways Ltd., parent company of the R.& E.R. (straying somewhat from his business card, he would often style himself "Engr. & Loco. Supt." when signing letters). As the railway's historians record, largely on the basis of recollections by then-apprentice Peter le Neve Foster (see R.& E.R.P.S. Newsletter 9, or page 41 of "The Bedside Ratty", compiled by W.J.K. Davies, 1974), Cauchi was utterly out-of-place in the happy-go-lucky Ravenglass environment- he even chose to stay at Barrow-in-Furness rather than Ravenglass when he visited the area. Arguably it was a good idea to have a responsible person among all the boys tinkering with their toys- but for all his seriousness and safety-consciousness, Cauchi simply did not have authority. His dire warnings were ignored, even after Easter 1922 when this happened:

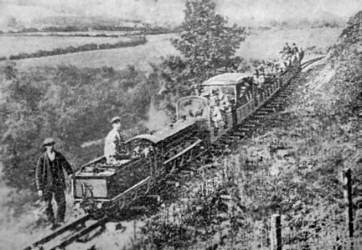

| The Times, 15 Apr 1922 HOLIDAY TRAIN ACCIDENT TWO CROWDED CARS OVERTURNED A serious accident occurred to a train near Ravenglass, on the Eskdale Railway, yesterday. A train of 12 open carriages was travelling down an incline when a coupling snapped. Two cars crowded with passengers were derailed and overturned, and many passengers were injured, three seriously. Miss Vail, Hulton-street, Brooksbar, Manchester, was crushed under a car, and her condition is critical. Miss Davey, Wellington-street, Millom, and Mr. Cox, of the same address, had their legs injured. The railway is a miniature one, which runs from Ravenglass up the Eskdale Valley. The majority of the people in the train were holiday-makers. |

|

Whitehaven News, 20 Apr 1922 ACCIDENT ON THE RAILWAY An unfortunate accident occurred on the Eskdale Railway on Monday and somewhat marred the holiday. As the train, drawn by two engines, with a full complement of passengers was travelling round the corner near Long Yocking a coupling broke and one of the coaches overturned. Some of the passengers jumped clear, but two ladies- Miss Vail, of Manchester, and Miss Davy, of Millom, were pinned underneath the coach and rendered unconscious, and Mr. Cocks, brother-in-law to Miss Davy, was hurt less seriously. Aid was quickly forthcoming, and the injured passengers were conveyed to Millom in Mr. Gainford's motor, and were on Tuesday night reported to be progressing favourably. This is the first accident to any passengers since the R. and E. Railway commenced running. Mr. James McGowan, J.P., C.C., with Mrs. McGowan, his wife, with ambulance man and others, rendered ready assistance, and the injured ladies were assisted to the residence of Mrs. Hartley, where Mr. and Mrs. McGowan were staying. The services of Dr. R. Todd and Nurses Batten and Docker were quickly forthcoming, and under their skilled attention made steady progress, and yesterday (Wednesday) had recovered to a considerable extent, although the effects will not wear off completely for some weeks probably. A young girl from Barrow-in-Furness had a miraculous escape from serious injury, and visitors from Barrow, Dalton, and other places were amongst those who also sustained cuts and bruises. |

| Millom Gazette, 21 Apr 1922 Accident on the Ravenglass and Eskdale Railway A regrettable accident occurred on the Ravenglass and Eskdale miniature railway on Easter Monday, owing to one of the carriages becoming derailed. Several of the passengers sustained injuries, the most seriously hurt being Miss Vail, who is on a visit to Millom from Manchester, and is staying with Mr. J. Cocks and Miss Davey in Wellington street. Mr. Cocks and his sister-in-law accompanied Miss Vail on Easter Monday, and in describing his experiences, Mr. Cocks said:- "We left Millom by the 10.28 train, joining the Eskdale train at Ravenglass. Everything went on all right until we got about midway between Irton Road and Eskdale Green, when I noticed there was something wrong with the third coach from the engine. I felt sure from its appearance that it had left the rails, and I stood up and shouted to the people in the coach, which was next to the one I was in. I may say the coaches were the open ones. The people in the coach evidently did not hear my warning, at all events they took no notice, and I jumped out of the coach and tried to reach the engine driver, but was unable to do so. Just then the coupling of the derailed coach broke, resulting in the overturning of two or three of the coaches, including the one from which I had jumped, and in which were my sister-in-law (Miss Davey) and Miss Vail (who is on a visit from Manchester). Miss Davey and Miss Vail were pinned underneath the overturned coach. It is strange the driver did not feel the effects of the coach leaving the rails, and had he noticed the derailment of the coach and immediately stopped the train the accident would probably have been prevented. However, he did not seem to know that a coach was bumping over the sleepers, and it was this coach which, when the coupling broke, caused our coach, which was next to it, to upset. The driver did not even know when the coupling broke that there were twelve coaches left behind, and proceeded for almost five minutes. When removed from under the upturned coach, Miss Vail was unconscious, and considerable time elapsed before she revived. Mr. and Mrs. James McGowan, of Whitehaven, who were on the train, did all they possibly could for Miss Vail, Miss Davey, and others suffering from shock or injuries. Brandy, hot coffee, smelling salts, etc., were soon provided, and eventually Miss Vail recovered sufficiently to be able to reach Miss Jackson's residence, which is close to the scene of the accident, and where, by the way, Mr. and Mrs. Hocking are staying. A messenger was sent to Mr. Gainford requesting use of his motor-car, and in this we were conveyed back to Millom. During the journey Miss Vail appeared to be suffering acutely from the shock and injuries, and had completely collapsed before she reached Wellington street. Dr. Todd and two nurses were summoned, and eventually Miss Vail was restored to consciousness. Miss Davey is badly bruised, but is doing well at present, although she is very sore. Miss Vail, under the careful attention of Dr. Todd and the district nurse, is also progressing satisfactorily. In jumping from the train I injured my leg, but not seriously. Mr Needham (of Barrow) also helped Mr. McGowan to attend to the injured. I consider that each coach would have three or four compartments, and if, as I understand, there were 15 coaches, each compartment containing eight persons [NB: this calculation is utter nonsense], the load which the two little engines were taking to Boot would be one of the heaviest that had ever been tackled by those miniature machines. Men jumped from the different coaches, and we did our best to retard those remaining on the rails, and in this I believe we were effective, as they were brought to a standstill. Another gentleman who gave valuable aid was Mr. James, agent for Mr. Campbell, the Liberal candidate. I understand there is a notice on the tickets of the Eskdale line that passengers travel at their own risk, but it is so small as to be barely discernible." Fortunately there were two Millom ambulance men on the train- Messrs. Crellin and Thornbarrow- who rendered first-aid to the injured. |

[The article continues with a look back over the railway's quirky history, quoted here, and the following week's issue has this brief note:]

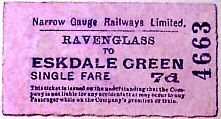

[The article continues with a look back over the railway's quirky history, quoted here, and the following week's issue has this brief note:] Although the railway's tickets included a note that the Company was not liable for accidents to passengers, Cauchi was also, quite naturally, worried that as his job included considerable responsibility for safety, he might be held personally liable by a litigous accident victim. He gave an idea of the numbers of passengers carried on the line- 500 were expected on one day the following week, and through tickets for Eskdale stations were available on both the L. & N.W. and Furness main-line railways, which included the R.& E.R in their timetable booklets (he provided the latest Furness timetable, showing 4 trains each way on weekdays- including the experimental 11.20 non-stop with slip coach for Irton Road- with one extra train on Thursdays and two extra on Saturdays; however, there were only two trains each way on Sundays).

Although the railway's tickets included a note that the Company was not liable for accidents to passengers, Cauchi was also, quite naturally, worried that as his job included considerable responsibility for safety, he might be held personally liable by a litigous accident victim. He gave an idea of the numbers of passengers carried on the line- 500 were expected on one day the following week, and through tickets for Eskdale stations were available on both the L. & N.W. and Furness main-line railways, which included the R.& E.R in their timetable booklets (he provided the latest Furness timetable, showing 4 trains each way on weekdays- including the experimental 11.20 non-stop with slip coach for Irton Road- with one extra train on Thursdays and two extra on Saturdays; however, there were only two trains each way on Sundays).| "Will you go and see drains at Boot Cottages at once- the whole lot are stopped up end to end- fact is they are not large enough for load & unless seen to at once there will be a fever break out. You know more about this job than I as I did not do it."

|

|

North West Daily Mail (Barrow) 19 May 1923 ESKDALE RAILWAY MR. HENRY GREENLY APPOINTED ENGINEER The Ravenglass and Eskdale Railway have appointed Mr. Henry Greenly, A.I.Loco.E., as engineer to the company. Previously, Mr. Greenly has been acting as consulting engineer to the railway, and during the progress of new work has been resident at Ravenglass. He has designed all engines that have been built for 15in gauge railways (as used at Margate, Rhyl, and other pleasure resorts, as well as those at Eskdale), that have been built during the last twenty years, and is known to the model engineering public as the author of several books on the subject. The designs for the new engine for Eskdale Railway goods traffic have just been approved and the order placed with Davy, Paxman and Co., Ltd., a well-known engineering firm at Colchester. It will be fitted with their patent valve gear. If reproduced in a size suitable to the full main line gauge, the engine would be the largest engine in the country, as well as the only one of its type. While entirely British in character, the design, in relative size, would approach that of many of the American mammoth freight engines. The weight of the new Eskdale 15in. gauge engine will be approximately five tons, and on the level it will pull a load of 70 tons. The length will be 22ft., height 46in., and width 3ft. 2in. The cab will be large enough to entirely house the driver. Turntables are now being erected at the Ravenglass and Dalegarth termini, and this will obviate the present necessity of engines having to descend the valley tender foremost. |

|

"Dear Baird, I am going to renew an acquaintanceship which dates back to the days of R.C. Radcliffe, not because I want something done, but because I would very much rather that your Department exercised or rather failed to exercise its powers under the Railway Gauges Act of 1846, which I believe are permissive and not mandatory. I don't know if you have ever heard of a little undertaking near my place in Cumberland called the Ravenglass and Eskdale Railway, which has violated this Act since its inception. When we started we approached the Board of Trade, not knowing that Public Works also had a say in the matter, and they were quite emphatic that we were not a railway under the meaning of the Acts, but rather an Entertainment, and they had no intention of interfering with us in any way, the line being a sort of glorified toy. Since then I have spent some thousands on it to encourage the district, and have opened a quarry up the line, on which it is entirely dependent to get its stone to the main Line, so naturally I am not anxious that eight years hard work should be thrown away by the malice of a bad man whose correspondence I enclose for your edification. Besides my own pocket, any interference with the Line would throw 30 or 40 men out of employment, and seriously affect the whole of the residents of Eskdale who depend on the Line for their Summer visitors and for their supplies, road transport being a desperate affair in that district. I saw Douglas Hogg the other day and we compared notes how Radcliffe's had been distinguishing themselves in various walks of life. The beggar put me in the witness box, but was very kind to me. Yours very truly Aubrey Brocklebank" |