These web pages present contemporary sources in an attempt to sort out the confused story of the massacre of British army officers near the village of Mahua Dabar, south of Basti in northern India, in June 1857, and the subsequent reprisals by the British. Please note that I have not (except for the substitution [N-word]) changed the quoted texts, which very often display 19th-century attitudes and terminology, plus a wide variety of attempts to transliterate local names and other words. However, I have sometimes added my own comments and clarifications [in italics in square brackets].

This page concludes the story, years after the brutal events of 1857. The main narrative of the Mahua Dabar massacre can be found here.

[My summary] This article claims that the "gair chiragi" [a Basti-area variant on "bechiragi" or "na chiragi," meaning "no lamps" and signifying "cultivated but not inhabited"] designation found on later documents was posted on a board outside the village immediately after the punishment burning, implying that the site was to remain uninhabited by official decree.

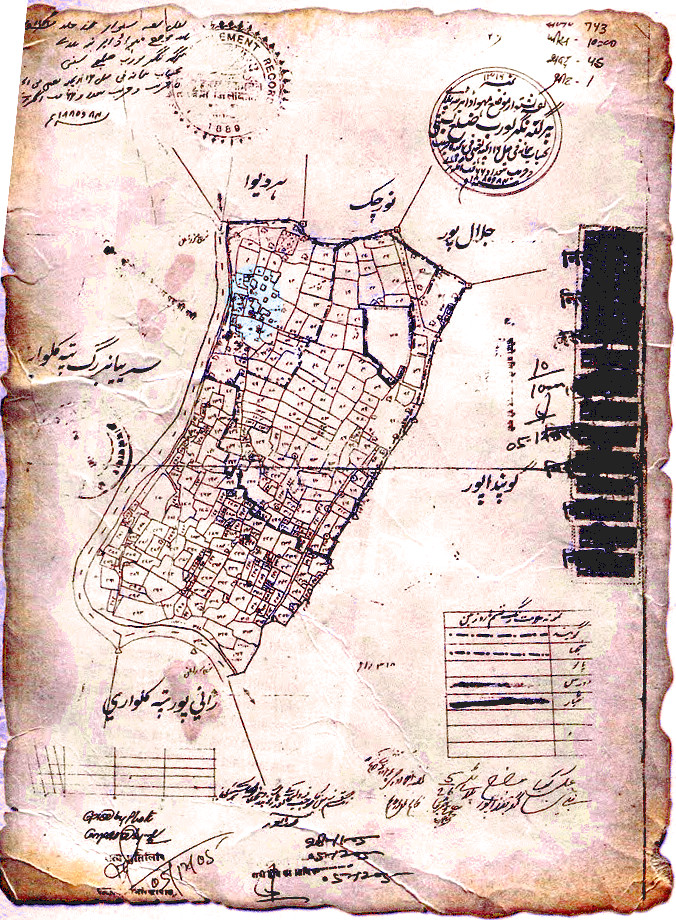

The problem with all claims that the village was ordered to remain permanently uninhabited is that in reality, a settlement has existed within the old boundaries, by the river in the north-west corner, since at least the 1880s, as shown (highlighted pale blue) on this 1889 plan:

[My summary] This article, about the punishment inflicted on the village by the British, names five revolutionaries who were hanged on 18 February 1858 in connection with the Mahua Dabar killings: Gulzar Khan, Nihal Khan, Gheesa Khan and Badlu Khan (Pathans) from Mahua Dabar, and Ghulam Khan from Bhaironpur, a short distance to the west. Also mentioned is the chaukidar Ruda Khan, who risked his job and his life to lure in the British soldiers.

[None of the above appears in the 2019 edition of "Dictionary of Martyrs of India's Freedom Struggle (1857-1947)" although various other martyrs from the 1857 war with the same names do]

p163: [describing the aftermath of the 1857-8 war] "... the Babu of Bakhira was hanged, and the Raja of Nagar avoided a similar fate by committing suicide in prison. Both their estates were confiscated, that of the latter being bestowed on the Raja of Bansi. ... Mahipat Singh, a Gautam, who rendered good service in guarding the Ghagra ferries in Nagar and secured the apprehension of the Mahua Dabar murderers, was given land paying Rs. 3,000 revenue."

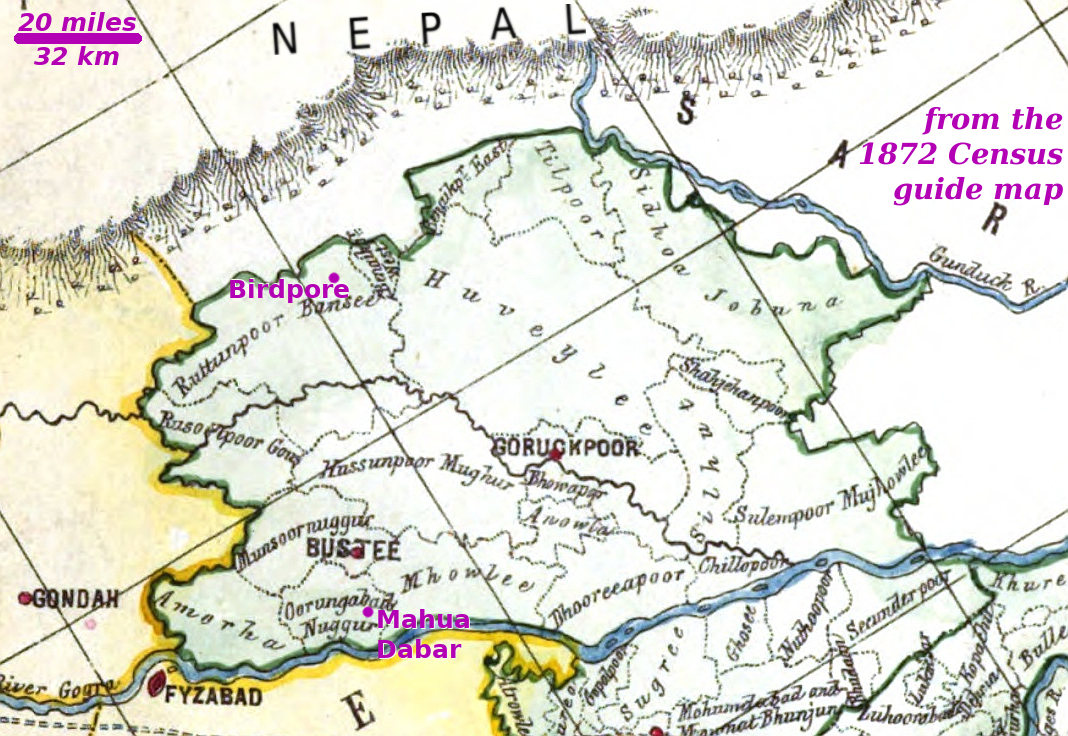

p71: "Goruckpore.- This and Bareilly are the only districts in the province in which the population has increased with anything approaching to rapidity ... But very marked differences in the progress of the people will be found ... for instance, Ruttunpore Bansie has increased 68 per cent.; Benaikipore West has trebled its population ... There are pergunnahs, on the other hand, where the population has decreased; thus, Amorha shows a decrease of 7 per cent.; Ourangabad and Bustee of 3 per cent.; ... Where these large increases have taken place it is doubtless to immigration that we must look for their cause. The decrease presents a question which, without local knowledge, I cannot attempt to solve. It is known, however, that the years 1864 and 1865 were years of great scarcity, if not absolute famine, in the Goruckpore District."

Appendix D, p37: [report from the District Officer responsible for Goruckpore]: "Whilst an increase of 351,639 is observable in the population of the whole district, there are parts of the district, chiefly in Circle 1 [Amorha, Basti and Nagar], where the population appears to have decreased since the last Census ... Circle 1 is the part of the district which suffered most from the annexation of Oudh, and from the Mutinies. Large numbers of the residents of Oudh used, under the native administration, to take refuge on this side of the Gogra: these people doubtless returned to their homes when Oude was annexed and a fair settlement assessed. Again, the rebel Rajahs of Amorha and Nugger used to entertain large establishments, and have thousands of men in their employ: these persons have not returned to this district since their masters were ousted. A very large increase is apparent in the population of Circle 2 [Bansi etc.]. Doubtless many of the former residents of Circle 1 have emigrated into that portion of the district where land was abundant and labor scarce. As Circles 1 and 2 adjoin each other, this emigration could be easily effected. In Circle 1 great distress was felt, owing to the dearness of food during the latter half of 1864; and some hundreds registered themselves as coolies for Demerara, Reunion, and other places.

The decrease in the population of the city of Goruckpore is, I am told by persons who appear to be deserving of credit, owing partly to the Mutinies and partly to the two sucessive seasons of great sickness which visited it in 1863 and 1864. Cholera, small-pox, and fever have carried off a very large number of the city people in these two years. Add to this that, owing to the high price of food at the close of last year, many poor people have doubtless left their homes in search of employment."

Table VI, p8: Pergunnah Ourangabad Nuggur, Hindoo agricultural population: 48,388 M, 43259 F; Hindoo non-agricultural population: 11,012 M, 9,710 F; Mahomedan [etc.] agricultural population: 3,962 M, 3,446 F; Mahomedan [etc.] non-agricultural population: 2,998 M, 2,418 F. Households 21,772; Total population 125,193

Pergunnah Munsoornuggur Bustee, Hindoo agricultural population: 60,202 M, 53,015 F; Hindoo non-agricultural population: 13,064 M, 12,100 F; Mahomedan [etc.] agricultural population: 6,513 M, 5,625 F; Mahomedan [etc.] non-agricultural population: 2,203 M, 1,973 F. Households 26,259; Total population 154,695

Table VII, p7: Population of Birdpore Grant, in Pergunnah Bansie: 13,671 (5th largest local population in the district)

p379: "A MUTINEER'S FATE.- One of the worst murderers of the mutiny has just been brought to justice. The story of his crime is thus told:- 'A number of fugitives from Fyzabad, among whom were Lieutenants Cautley, Thomas, Lindsay, and English, of the 22nd N.I., and Lieutenant Ritchie, of the 13th Light Field Battery, had made their way towards Azimgurgh as far as a village called Mahooadabur, on the bank of the Manorama, in the Goruckpore district. Lindsay was cut down as they were preparing to cross the stream, and the rest were shot down or beaten to death with clubs, with the exception of two only- Lieutenant Cautley and Sergeant Busher, who gained the opposite bank. But they were closely pursued by one Jafir Ali, an influential zemindar, and others. Cautley became exhausted, and was easily overtaken, in spite of the good offices of a friendly peasant. He was knocked down by a blow from a lattee, and as he was attempting to rise to his knees Jafir Ali deliberately shot him in the breast. From that time till quite recently Jafir Ali has been a fugitive, and is said to have made a pilgrimage to Mecca. On his return he was arrested, and the Judge of Goruckpore (Mr. Benson) sentenced him and three others to death. Before the High Court at Allahabad, North-West Provinces, the Government advocate said he would not press for a capital sentence except against Jafir Ali, the ringleader and actual murderer. The Court, Mr. Justice Turner and Mr. Justice Turnbull, after some consideration, acquitted the other prisoners, but confirmed the sentence of death against Jafir Ali.' "

[This story appeared in Indian domestic newspapers at the beginning of March, originating apparently in the 'Pioneer'- then published in Allahabad, U.P.]

THE CHARGE AGAINST A MUTINEER OF 1857.

from the Times of India -On Friday, in the Girgaun Police Court, [in Bombay/Mumbai] before Mr. Showell, Nubee Khan Lalkhan, a native of Mowa Dabur, in the N.W. Provinces, who was concerned with two of his brothers in the massacre of some Europeans, during the rebellion of 1857-58, was brought up on remand and charged with having been an accessory to the murder of several Europeans (whose names are at present unknown) in the Goruckpore zillah, N.W.P., during the rebellion of 1857-58. No reply having been received from the District Superintendent of Police, Goruckpore, the magistrate remanded the accused for a fortnight.

[In the version of the report in The Pioneer (Allahabad), 13 Jul 1871, the name of the accused is given as "Nubee Khan Lall Khan". I don't think this man is the same as the Mewati named Lall Khan who was co-defendant in the "Durriabad Murder" case that September]

AN EPISODE OF 1857.- The sun was blazing hotly down on the Gogra river on the 9th of June 1857, as two-and-twenty British officers embarked from the Oudh shore in four open boats, hoping to reach the friendly shelter of Azimgurh, and thus elude the murderous pursuit of the mutinous soldiery at Fyzabad. Befor them, across the river, lay the plains of Goruckpur (now of Bustee), stretching south and east- dotted with villages and mango groves: behind them was Ajodhia with its shrines and temples, domes and towers. The boats soon separated. The foremost, with seven officers on board, shot far ahead: but hardly had it made 20 miles down the river, when it was attacked from the Oudh bank by a band of rebels under the Nazim's standard, and the fugitives were compelled to put to the left shore, and start across country for Bustee (some 30 miles distant) where they knew there were still European residents. Of the seven, two were drowned in crossing a river that lay in their path, while the remaining five, foot-sore and weary, arrived at the Captaingunj tehsil on the morning of the 10th. Here they were joined by two others from the fourth boat; and thus strengthened, the little band (six officers and one sergeant) resolved to press on and take their chance. At Captaingunj they met with every kindness. The tehsildar supplied them with food, money, and horses; but strongly urged them to abandon the idea of seeking safety at Bustee, representing that their best course was to make for Gaeghat (a small township further down the Gogra), and thence take boat to Dinapur. Fatal as this advice turned out to be, it is believed to have been given in all good faith; and the party set off under the guidance of three chuprassies on their perilous journey.

About eight miles from Captaingunj, picturesquely situated on the banks of the Manorama, lay the village of Mowadabur, then a famed bazar, where Mahomedan cotton-printers congregated in large numbers and drove a thriving trade. The village itrself stood on an eminence overlooking the river; and here, towards evening, led by the three chuprassies, the fugitives wended their way. With no suspicion of treachery, they gladly assented to the proposal of one of their guides, that he should go in advance and procure refreshment for the travellers in the bazar: and thus, under a friendly guise, the wretch went forward to plan their destruction. It was no difficult task to inflame the bigotry of the Mowadabur mob; and as the British officers passed through, they saw- only too late- how grievously they had been betrayed. Desperate as their situation was, they pressed bravely on towards the ford that lay beneath the village, while close behind came the fierce crowd thirsting for the blood of the accursed unbelievers; and armed, all of them,, with clubs, swords, and matchlocks. There was no need, and little inclination, to drive their victims to bay; but once they had commenced to ford the stream the carnage began. The last to enter the water was struck down from behind, and instantly cut to pieces; four were butchered on the other bank by the cruel mob: two alone survived. One (the sergeant) was a strong man, and, running for life, soon distanced his pursuers. But his companion- fresh from an English home- had exhausted his strength. A kindly peasant gave the weary stranger a drink of water from a roadside well, and bade him God-speed: but before he had gone much further he was overtaken, and while one man struck him down with his sword, Jafir Ali (an influential zamindar) exultingly shot him dead as he lay.

So much for the tragedy: now for the sequel. Of the treacherous chuprassies who betrayed their trust, and handed over the party to destruction, one expiated his crime on the gallows; the other two were condemned to transportation for life. The brutal murderers of the young officer across the river cumber the earth no longer. He who struck him down died while under trial, having been captured in Nepal. Jafir Ali wandered scatheless for twelve years long; pilgrimaged to holy Mecca, and became a faqueer [=fakir]. But some instinctive impulse- we may call it Fate- urged him to look once more on his native village, and re-visit the scene of the massacre: for who could recognize in the pious mendicant and devotee the once notorious Jafir Ali? But his end was near. While crossing the Gogra at Tanda he was recognized, apprehended by the Police, taken to Bustee, tried, condemned, and executed.

As to the Mowadabur crowd, by whose hand five officers had fallen, some thirty of the ringleaders were proclaimed, and rewards were offered for their apprehension. Five of these suffered death in February 1858, some were released on the ground of insufficient evidence, but the village itself was razed to the ground. At the close of 1869, the Bustee Police captured several of the survivors, and three were condemned to death by the Sessions Judge (along with Jafir Ali), after an elaborate and exhaustive trial. [i.e. the trial reported in March 1871, as above, implying that it took around a year to gather witnesses] But for reasons best known to that august body, the High Court Judges were pleased to cancel the sentence and release the prisoners, so three blood-stained ruffians now live in peace within sight of the ruins of Mowadabur.

There still remained, at the beginning of 1871, five of the proclaimed offenders, the crème de la crème of the Mowadabur murderers, and for whose apprehension Government still offer rewards: four Mussulmans and one Souar- of whom the latter had been strangely conspicuous in the carnage. Very lately we chronicled the capture, in Bombay, of Nubba Khan, one of the five, who had sought in vain for concealment a thousand miles from the scene of his crime. As his case is still sub judice, we forbear to remark on it for the present. But it is to be hoped that the Bustee Police will zealously follow up the good work already done, and only let the sword of justice be sheathed over Mowadabur when the last of the murderers has met his doom.

[suggests that the British spent a decade punishing India for the war of 1857, killing perhaps as many as 7.5 million people in the United Provinces; reviewers of the work suggest that Misra failed to take sufficient account of the scale of migration]

p294 (Table V, Bustee): Pergunnah Aurangabad Nagar: Population totals, Brahmans + Rajpoots + Bunniyas, 14,916 M, 13,298 F; Other castes, 44,544 M, 39,406 F; Mahomedans 6,345 M, 5,969 F. Total: 124,478

Pergunnah Mansurnagar Basti: Population totals Brahmans + Rajpoots + Bunniyas, 16,245 M, 13,958 F; Other castes, 64,125 M, 56,266 F; Mahomedans, 9,687 M, 8,319 F. Total: 168,600

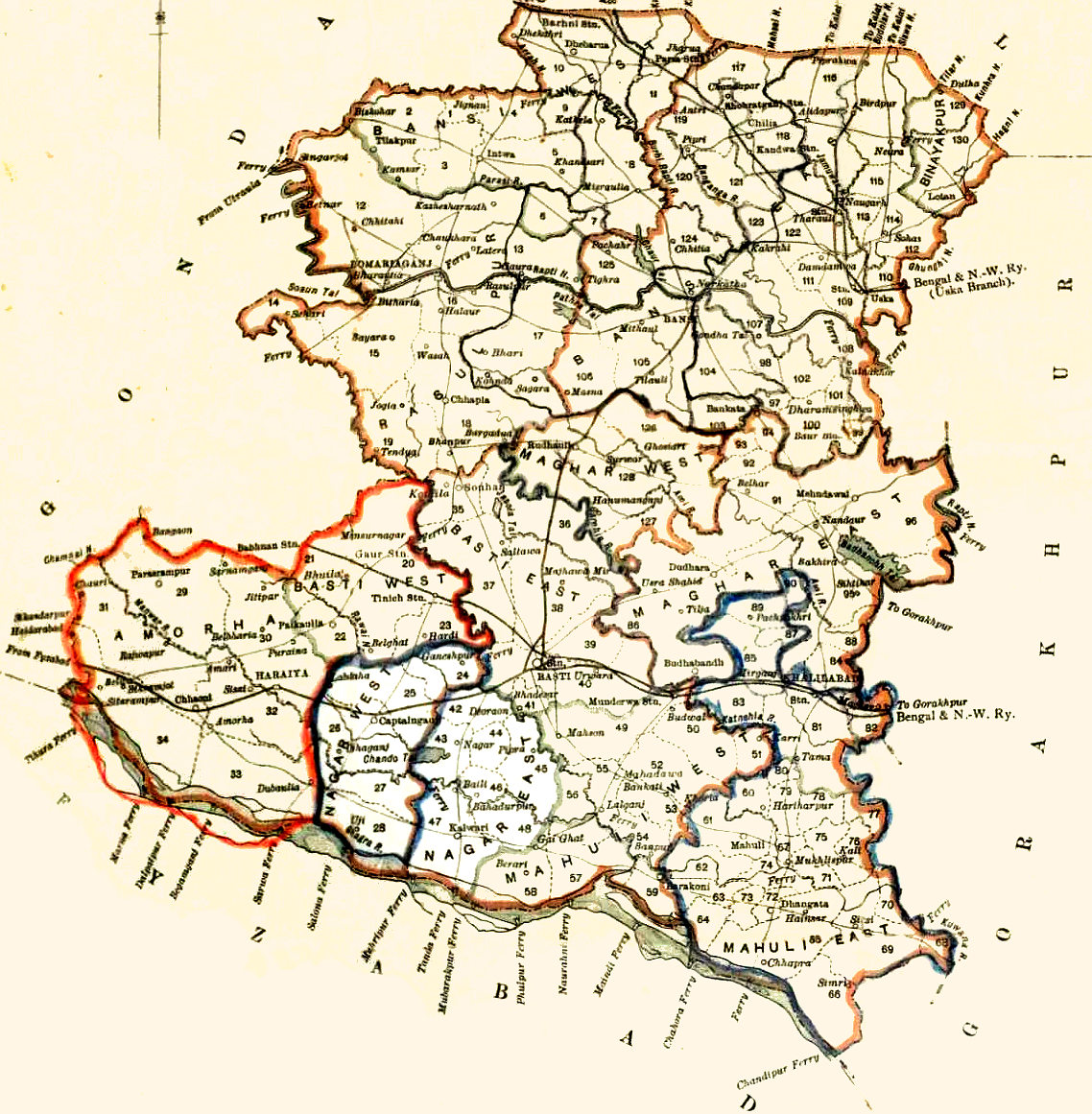

p788: "Nagar has but one manufacture of any note- the chintz and gilt cloths prepared by the cotton-printers (Chhipi) of Bahadurpur. These stuffs are extensively sold not only in the district itself, but even in Butwal of Nepal The main trade of the parganah is as usual its trade in grain; but there is also some commerce in home-made or imported cloth, and in imported spices, tobacco, cotton, copper and brass utensils. The principal marts are Bahadurpur, Pandur, Kalwari, and the old parganah capital Nagar, where a small yearly fair is held in April-May."

p194: "except Basti, the headquarters of the tahsil and district, there is no town and scarcely any large village. The principal markets for country produce are at Basti and Deoraon in pargana Basti East, Bahadurpur, Kalwari, and Xagar in Nagar East, and Lalganj and Gaighat in Mahuli West. But besides these, as will be seen from the list given in the appendix, there are many petty village bazars, where country produce finds a ready sale and simple necessaries can be purchased. The only manufactures of any note are the chintzes and gilt cloths prepared by the cotton printers of Bahadurpur and the printed fabrics of Lalganj."

p249: [describing Nagar East Pargana]: "There are no fewer than 480 inhabited sites, but none are of any size. Kalwari indeed is a very large village, and so is Nagar itself, but in each instance the place consists of a collection of scattered hamlets; besides these, Pipra and Bahadurpur alone contain over a thousand inhabitants. Markets are held at these places and a few others: the trade is chiefly in grain, but there is some commerce in cloth, spices, tobacco, cotton, copper and brass utensils. The only manufactures are cotton-weaving and cotton-printing at Bahadurpur; the printers also prepare chintz and gilt cloths, which are sold not only in this district, but also in Nepal."

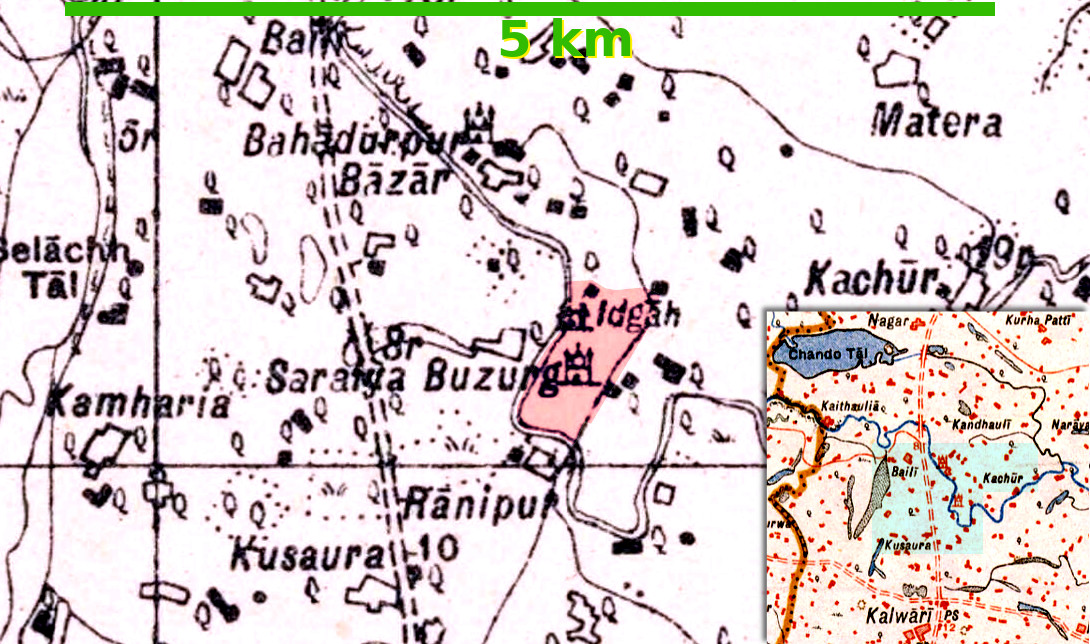

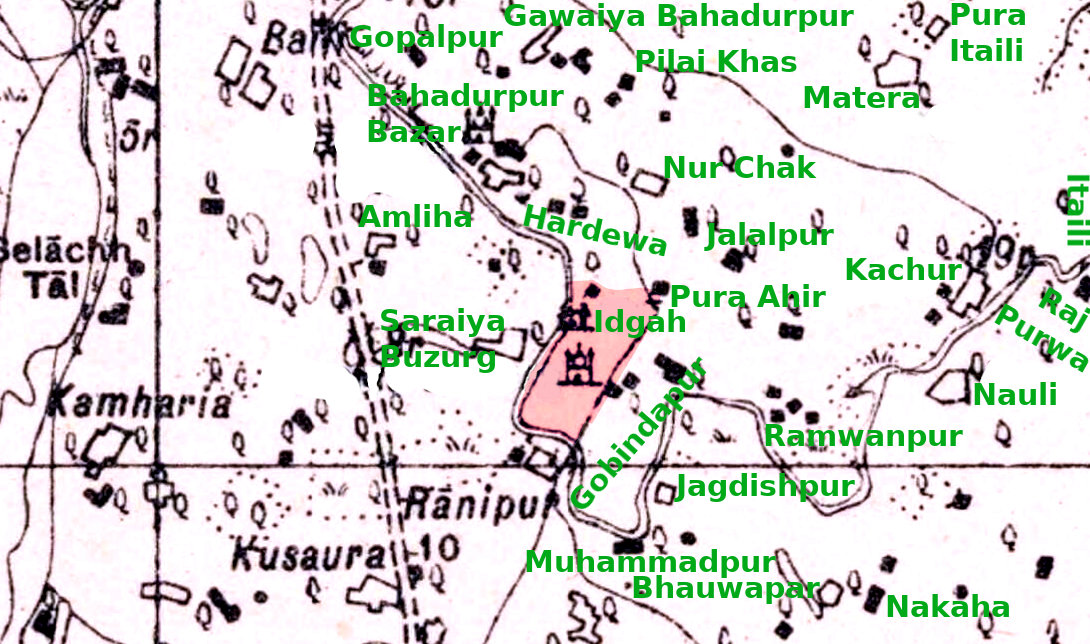

Survey of India maps of the area south of Basti have avoided using the name Mahua Dabar (or any spelling variant). Here's the area on a 1922 Survey map (surveyed almost a decade earlier, but delayed due to the First World War). The community which appeared on the 1880s village map is labelled "Idgah"- a name referring to open-air sites used for Muslim festivals (often spelled Eidgah), one of which does indeed exist here, overlooking the river, indicated on the map with the appropriate symbol.

Modern maps have added many more place-names, but have not amended "Idgah". Here are names from a more recent map superimposed on the 1922 version. Before we leave these maps, note the symbol for a functioning mosque in the heart of the pink-tinted village area, south of the Idgah, where in the 1990s was only a roofless shell (indeed, the symbol also appears on editions of the map up to at least 1975, though that may be the result of inadequate revision). It seems that the British demolition in 1857 had nothing to do with the ruin of the mosque.

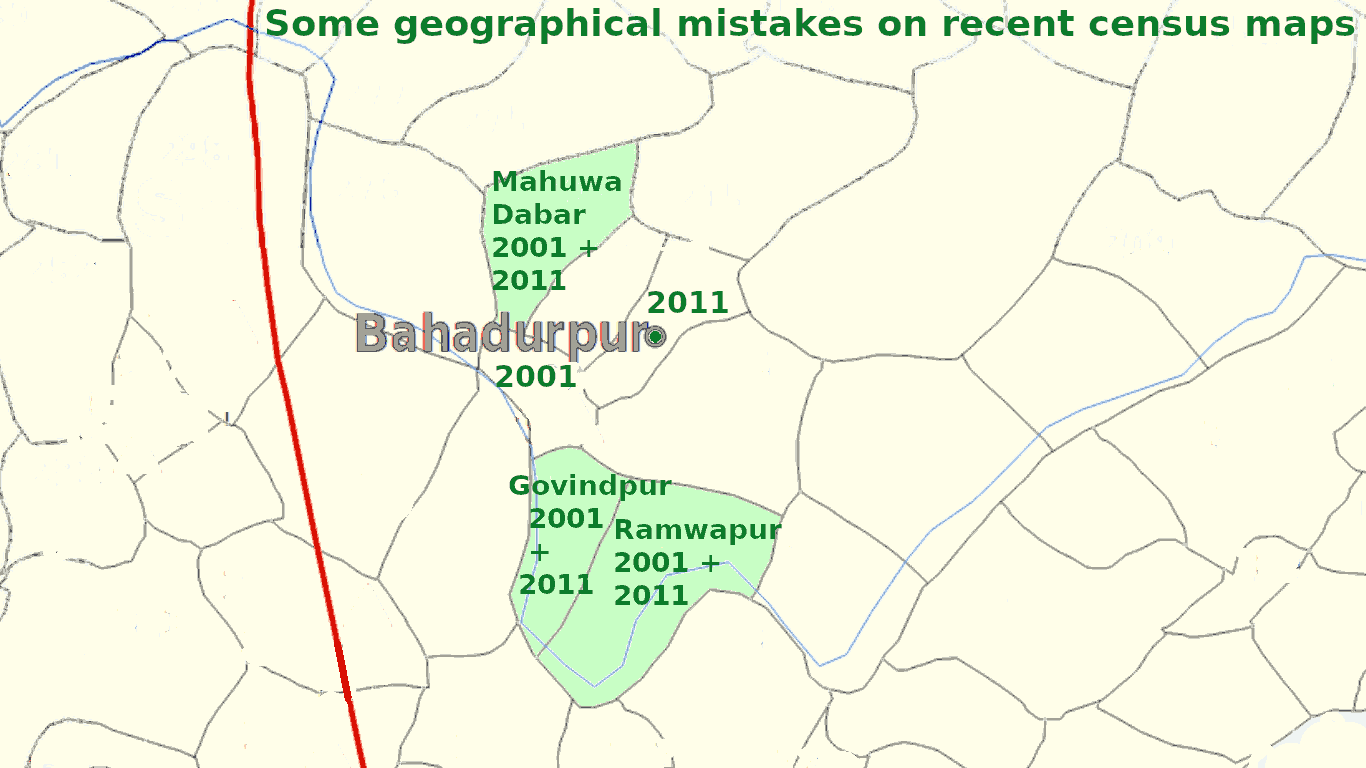

The omission of the name of Mahua Dabar from Survey of India maps may have had some ludicrous long-term consequences. Census enumerators were aware that the place existed, and was populated, but the makers of maps to accompany the census reports did not know where to put it, and in recent censuses it and other places nearby have wandered around! I have not seen a map from the 1971 census, (where it appears in roughly the right place in the list of communities: 919,Ramwapur; 920,Govindapur; 921,Mahuwa Dabar; 922,Herdewa; 923,Bahadurpur) or 1981 (where it may perhaps be slightly misplaced: 1127,Ramwapur; 1128,Mahua Dabar; 1129,Govindpur) or any details from 1991, but in 2001 and 2011 things definitely go awry, as shown here:

The uncertainties of the census mapping have been reflected in commercial map and satellite websites / apps, as seen in these examples, all accessed in December 2019:

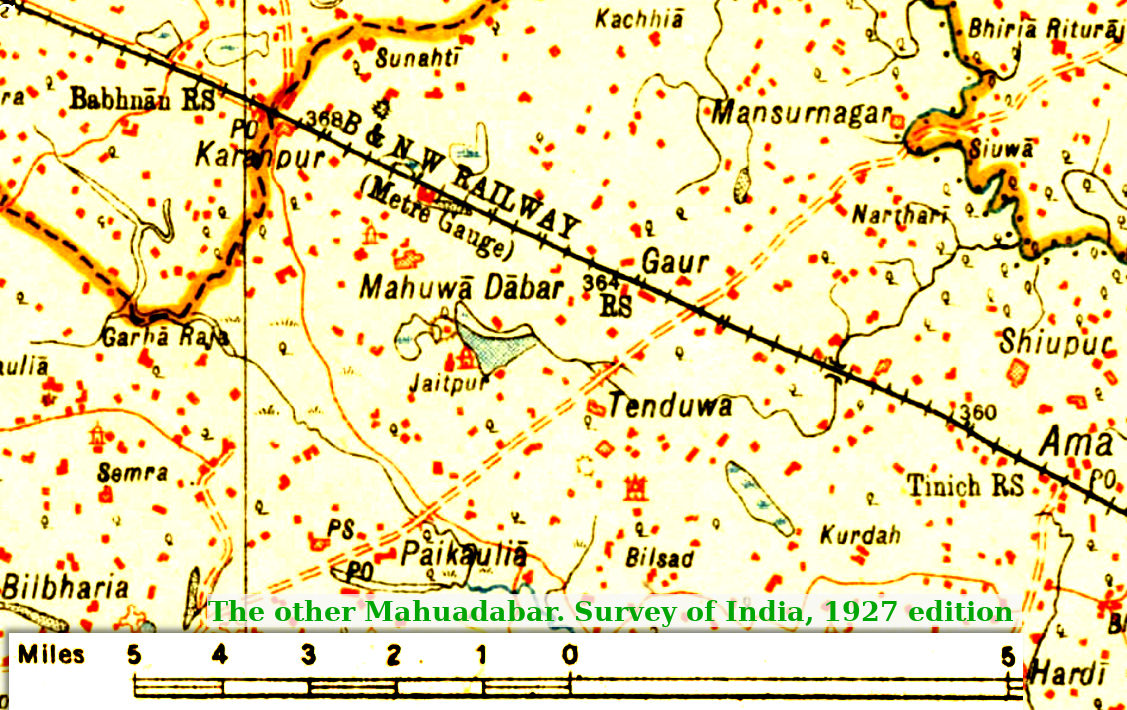

p610: [Alexander studies Buchanan's statistics, compiled around 1813, for the Basti part of the Gorakhpur district, which had a total area of 2,551 square miles, inhabited by 102,478 families (Mahuadabar Police Circle containing 212 square miles and 10,226 families) and notes some significant changes, such as:] "His Sanichara corresponded pretty closely with pargana Mahauli; his Mahuadabar with parganah Nagar; and his Khamaria with parganah Amorha. ... The Mahuadabar which gave its name to the circle so called was destroyed during the Mutiny, and must not be confused with the Mahuadabar of parganah Basti."

p789 footnote: "The head-quarters of the circle, Mahuadabar village, was destroyed during the Mutiny, and must not be confused with the small mart thus called in tappa Atroh of parganah Basti. The name simply means 'the pool of mahua trees;' and and should be common enough in a district where both mahuas and pools are numerous."

p158: [describing the fate of the British officers, who] "... left their boats and proceeded by way of Amorha to Captainganj, where they were warned by the tahsildar to avoid Basti; they then turned towards the north, but at Mahua Dabar in pargana Basti West they were treacherously killed ..." [In reality, of course, they turned south-east and died at the Mahua Dabar in pargana Nagar East]

[describing the area around the archaeological site called the Dih of Bhuila, north-west of Basti]

p149: "to the north-west, there is the large village of Mahua Dabar which is mostly inhabited by a set of so-called Rajputs of the Kalahans tribe, who have a very questionable right to the position which they occupy."

p152: "The Kalahans Rajputs of the neighbouring village of Mahua Dabar say that when they first came to this locality Atroha was in the possession of the Bhars. In fact, according to another tradition which I heard, it would appear that the ancestor of the Kalahans Rajputs was in the service of the Bhar Raja; and that on the occasion of a marriage feast among the Bhars, they (the Bhars) got drunk, when the Kalahans and his followers arose and slew all the Bhars and took possession of their property."

All that Abdul Latif Ansari, 65, had to go by was a tattered, hand-drawn, two-century-old map and family lore about how his forefathers had suffered twice in British hands.

It was enough to keep bringing the Mumbai businessman to Basti, eastern Uttar Pradesh, for 14 years to search out his ancestral home, lost in the mists of time for a century and a half.

...

In the early 19th century, the East India Company, eager to promote British textiles, had cut off the hands of hundreds of weavers in Bengal.

Twenty weavers’ families from Murshidabad and Nadia had then fled to Awadh, whose nawab resettled them in Mahua Dabar and allowed them to carry on with their livelihood.

Many of the first-generation weavers had already lost their hands, but they taught the craft to their sons and the small town of 5,000 people soon became a bustling handloom centre.

[Here follows a short summary of the massacre of British officers]

On June 20 that year, the 12th Irregular Horse Cavalry surrounded the town, slaughtered hundreds and set all the houses on fire. The Raj decreed that no one could live in the place from then on. On the colonial revenue records, the area was marked gair chiragi (non-revenue land). ...

It is indeed likely that the local weavers had migrated from Bengal, but by the early 19th century, the Goruckpore and Basti area was already under British control, in return for military service to the Nawab of Oudh. The migration may have occurred a generation or two earlier, perhaps due to famine in British-governed Bengal. It was almost certainly not prompted by the British cutting off weavers' hands: I have compiled a separate page explaining the origins of that story, for which there is not a shred of evidence.

p30: [Introduction] "A MAN'S QUEST TO trace his roots has unearthed an atrocious slice of Raj history. Of how the British, a little over 150 years ago, massacred hundreds in a small town in Uttar Pradesh, razed it to the ground, and wiped out all mention of the place from the records as vengeance for the townsfolk's participation in the 1857 uprising."

p34: "Octogenarian KM Pandey, former principal of another prominent college in Basti, remembers that his father, a private tutor to the Raja of Pukharni near Basti, used to hear about the massacre and destruction of Mahua Dabar at the royal household.

Harish Chandra Barnwal, 82, whose forefathers were zamindars near Bahadurpur, says: 'I used to hear from my grandfather of the obliteration of Mahua Dabar and the British decree that no settlement could ever come up at that site." ... Renowned historian Hari Shankar Srivastava of Gorakhpur University also confirms the Mahua Dabar incident.

The only structures that miraculously escaped the British were two mosques on a mound near the Manorama River." [What was the miracle which preserved the mosques? Nobody seems to have asked that simple question, or the question implied by Survey maps, as noted above: when did the mosques cease to be maintained and lose their roofs?]

[If the title didn't give sufficient clue, here's a sample translation:] "The heads of the residents who came to the clutches of the British were chopped off there. Their dead bodies were torn to pieces and thrown away. ..."

If you have read all my web pages on Mahua Dabar, you will know that I have found a very large amount of evidence about the events of 1857-8, confirming in detail the story of the destruction of the village by troops under the command of William Peppé. The absence from my pages of any evidence about a massacre there by the British, as described by Dr. Dwivedi or Jaideep Mazumdar is not my fault. If anybody can produce an eyewitness account of that massacre, or archaeological evidence, I will include it (please supply images of the original document, and a transcript of the text).

David Bradbury, 2020

Just in case you have missed any of the earlier pages in this summary of the Mahua Dabar story, here's a list of links:

You may also be interested in another Missed History resource: a database of famines in India, 1500-1767