SAMUEL TAYLOR COLERIDGE

VISITS ESKDALE, 1802

In August 1802, Samuel Taylor Coleridge undertook a walking tour of the western Lake District. Having studied William Hutchinson's History of Cumberland, with its detailed information on the various parishes and townships, he made notes, and a copy of the relevant section of the map (which, correctly but unfortunately, gave the name "Scafell" to the whole ridge from Slight Side to Great End, and did not show details of such features as Mickledore) then set off from his home at Keswick on August 1. For some sections of his journey, including much of the walk through Eskdale, details survive from both the notebook he took with him and from a descriptive letter he wrote in episodes as he went along, to his beloved Sara Hutchinson (not to be confused with the Sara to whom he was actually married). This summary attempts to combine the information from the two sources (but it omits the details of the most famous and oft-reprinted passage, the descent to Mickledore from Scafell [the link given is to the local Mountain Rescue website]). The letter episodes are numbers 450 to 452 in "Collected Letters of Samuel Taylor Coleridge", Vol. II (1956), edited by Earl Leslie Griggs; the notebook sections are numbers 1218 to 1222 in "The Notebooks of Samuel Taylor Coleridge", Vol. 1 (1957) edited by Kathleen Coburn.

By August 5, he had reached Wasdale Head, and his next goal was Eskdale. He could have taken the old road straight over Burnmoor, but of course what really attracted him was Scafell, so he turned off soon after sighting Burnmoor Tarn, following a rushing stream up the flank of the mountain (he may have contoured round to Hardrigg Gill, for he gives the impression of having seen Burnmoor Tarn only from a distance). After visiting the summit, he headed north, finding shelter from the wind in a most dramatic situation, overlooking Hollow Stones (his host at Wasdale Head, Thomas Tyson, had helpfully named for him some of the main features as seen from the valley) and even in sight of his home, with Borrowdale and Derwent Water visible in the slight haze. Here he sat and wrote the latest instalment of the descriptive letter, before setting off in the direction of what he thought was Bowfell, via a low ridge below the cliffs on which he had so happily sat. He did not know the name of the low ridge- Mickledore- nor the impossibility of climbing down to it directly from Scafell without proper equipment. As is often the case, not knowing that it was impossible, he went and did it. When he could no longer walk or scramble, he simply dropped from ledge to ledge- which cut off his retreat- and made the last descent by shimmying down a rock cleft, which would almost certainly be Fat Man's Agony at the foot of Broad Stand (though whether he got down to it by the currently accepted route is doubtful- rock falls and the activities of climbers have allegedly changed the formations since his day).

However, the descent had taken a great deal of time and effort, and the weather appeared to be deteriorating (he also had no food, but that never seemed to bother him). Rather than continue to "Bowfell", he therefore headed straight down, following the right-hand of the two parallel streams, towards Eskdale- observing that the river below looked just like a broad road. He was most impressed by the series of waterfalls we know as Cam Spout, and by the boulders we call Sampson's Stones- though from a distance he had thought one of them was a bothy, in which he could shelter from the impending storm. He found shelter instead within the cluster of five old sheepfolds near the Stones- where he discovered the shepherd's shears and red marking dye- then when the weather cleared, he followed the shepherds' track southward. Eventually, he came upon the zig-zag peat-road down by Scale Gill and followed it down to the bridge, admiring the wooded waterfall and the rapids down to the Esk, then he continued along the track through the "sweet pretty fields" (the bridge marking the highest point of cultivation in the valley) to Taw House (marked on his map as "Toes" and pronounced "Te-as").

The owner of the farm, John Vicars Towers, put him up for the night and gave him a quick geography lesson, which he scribbled in his notebook. The cliff-top perch where he wrote his letter was on Broad Crag (now Scafell Crag)- pronounced by Towers as "Bre-ad". What he thought was Bowfell, was actually Ill Crag, in front of which was Doe Crag (now spelled Dow- but then apparently including the whole ridge up to Scafell Pike summit) above the parallel streams down the How. Towers named for him all the features of the dale-head: Great End beyond Ill Crag, then Esk Course (as Coleridge heard it) with the river running down through Esk Course Bottom; then Tongue (probably not the modern Tongue but the Esk Pike / Pike de Bield ridge), Hanging Knot, Bowfell, Adam a'Crag (apparently referring to a broader area of Crinkle Crags than it does today), Yew Bank (said formerly to have been covered with yew trees, though few were to be seen by 1802), Hard-Knot and Low Fell (seemingly the ridge below Harter Fell). Below Bowfell was Long Crag (apparently including the modern High & Low Gait Crags) overlooking the upper Esk, and behind that Green Hall (i.e. Green Hole).

Here's a funny thing. In his notebook entry written at the top of Scafell, Coleridge clearly thinks Bowfell is not far beyond the "low ridge" and appears unaware of names like Ill Crag and Doe Crag- but the letter to Sara Hutchinson, which he claimed to be writing in the same place, does name Doe Crag as his immediate goal, and mentions other features from the geography lesson. It seems that the letter as eventually sent (posted in Ambleside on the 8th) was actually a revised copy of the one he had been writing as he went along; perhaps it had become rather messy and dog-eared, or perhaps he felt that the mistakes in the original made the tale of his dramatic descent to the ridge look much more like the action of an idiot than a man of decisive boldness.

Towers took Coleridge back up onto the fells the next morning to show him what Hutchinson had indicated as Eskdale's most notable tourist attraction. This was a stone apparently marked with human and animal footprints, at the foot of Buck Crag. It seems that they climbed straight up the fellside from Taw House, then turned sharp right (so that Coleridge thought he was heading due east) across the heathy upland south of Scale Gill. They crossed near the top of Scale Gill, to Moddoch (or Maddock) How, then continued northward to Buck Crag. Having seen Cat Crag on the left, Coleridge was further tantalised with the appearance on his right, in the swirling mist, of a line of half-a-dozen triangular crags. Sadly, his guide only knew the names of three- the first and second in the row (called Broad How and Round Scar: the latter still appears on large-scale maps) and the last- Dinny How. Coleridge states that just beyond this row is Brock Crag- which happens indeed to be the modern name of the great crag overlooking the Esk, just to the south of the row. The mist also revealed glimpses of the great crags higher up the valley- Spout Crag (i.e. Cam Spout Crag) and Earn Crag (most probably the modern Horn Crag, also formerly known as Orn Crag).

Towers took Coleridge back up onto the fells the next morning to show him what Hutchinson had indicated as Eskdale's most notable tourist attraction. This was a stone apparently marked with human and animal footprints, at the foot of Buck Crag. It seems that they climbed straight up the fellside from Taw House, then turned sharp right (so that Coleridge thought he was heading due east) across the heathy upland south of Scale Gill. They crossed near the top of Scale Gill, to Moddoch (or Maddock) How, then continued northward to Buck Crag. Having seen Cat Crag on the left, Coleridge was further tantalised with the appearance on his right, in the swirling mist, of a line of half-a-dozen triangular crags. Sadly, his guide only knew the names of three- the first and second in the row (called Broad How and Round Scar: the latter still appears on large-scale maps) and the last- Dinny How. Coleridge states that just beyond this row is Brock Crag- which happens indeed to be the modern name of the great crag overlooking the Esk, just to the south of the row. The mist also revealed glimpses of the great crags higher up the valley- Spout Crag (i.e. Cam Spout Crag) and Earn Crag (most probably the modern Horn Crag, also formerly known as Orn Crag).

Though Buck Crag does not appear on the Ordnance Survey- and hence not on any other modern maps- the location of the wonderful stone (which Coleridge christened the Four-foot Stone, though Hutchinson had claimed only three) has not been lost. The trouble is, as Alan Hankinson found when attempting to follow in Coleridge's footsteps for the book "Coleridge Walks the Fells" (1991), even knowing that it is by the path below what is now called High Scarth Crag (which is in effect two crags- so possibly one should be Scarth Crag, the other Buck Crag) is not enough to identify it. You'll almost certainly have to get yourself a local guide who can trace the foot outlines, as Coleridge did, and as Hankinson eventually did (after two fruitless solo excursions). I have probably seen the stone myself without being able to distinguish the various shapes- which are, for the record, a little child's shoe 10cm long, a boy's shoe 24cm long (looking as if it is in a mire), a large dog's paw, and a "beast's" (i.e. probably cow's) foot 15cm long. The visible size of the whole stone was then 91 x 82 cm, but the markings were all within an area about 52cm across.

And the confusion continues: Coleridge reports that after admiring the stone, he ran up to Brock Crag- but this seems to imply that his Brock Crag was at the North end of the row of six, not the South. Such a location would also be best for his next geography lesson- again he admired "Earn Crag", and in his notebook he drew a little plan showing the head of Eskdale. Then back to Taw House, to write another instalment of The Letter, halted by the call to dinner [i.e. what some might call lunch].

And then he had to be on his way, as he planned to spend the night at Ulpha. He set off down the valley, noting the inclosure walls on the steep, tree-dotted fellside, intrigued by the way middle Eskdale is divided in two by low hills (he thought it ought really to be called the "Eskerdales") and full of admiration for the lovely dale houses "nested in Trees at the foot of the fells". Eventually, where the valley finally ceased to be divided in two, he crossed a bridge over a beck with "well wooded Banks", which he thought (wrongly) came from Harter Fell, near to two or three houses. This was, as he later found, Whillan Beck, so the houses may include the Vicarage; from here he could also see the dramatic view back towards Scafell, with the old Burnmoor road climbing up from Boot. The division of the valley by low hills ceased within a short distance and the beck joined the Esk, across which he could see a "pretty regular farmhouse" backed by a lushly-wooded hillside. For a few hundred paces the river got closer to his road until it was right alongside, but then swung away again. It looks as if he met one of the locals somewhere around here, perhaps near Spout House, for his notebook contains several lines of explanation and corrections: the name and source of Whillan (or possibly "Whillah") Beck; the true location of Harter Fell, next to Low Fell; the name of the rocky and woody fells to his right (the crags starting to disappear into a blanket of young woodland)- Eskdale Moors; the name of the fells opposite- Birker Fells; and the identity of the "regular" house- Mr Stanley's shooting seat (i.e. Dalegarth New Hall- now called Dalegarth Hall Cottage). The river has also swung back towards the road, with an islet visible across the hayfields (this, on the west side of the big meander near Spout House, is not really an islet any more as the stream round its eastern side no longer flows most of the time).

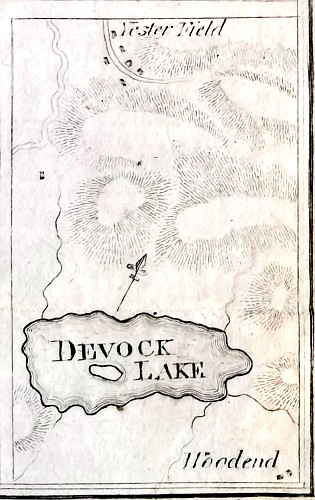

Devoke Water from John Housman's 'Descriptive Tour, and Guide to the Lakes' (1800) |